Last week, I skipped class.

This may come as a surprise, as I am someone who is very invested in my own learning and find great joy in attending my Montessori adolescent diploma course, which is the class that I skipped.

The reason I skipped class hits at the core of my drive for working in education. I am an educator because I believe in the potential for education to be transformative for all students. I believe that education can be a space for collective liberation of students, teachers, and communities, and that this outcome occurs when we step into the work of learner-centered, antiracist education.

I am currently participating in an antiracist working group with Embracing Equity, and in our first session, we discussed the role of an “ally” versus a “co-conspirator.”

Allies will notice when situations are unjust and will let those affected know that they are aware, but may be resistant to disrupting unjust events and actions as they occur. They often prioritize their own comfort over changing the status quo. Co-conspirators, on the other hand, actively disrupt racism, white supremacy, and injustice, putting their bodies on the line (figuratively and/or literally) to be active agents in creating a better world.

I am on a journey to be a co-conspirator in my own life, inspired by the dialogue this Embracing Equity group.

“Four Dead in Ohio”: Does No One Hear the Rhyme?

The far-too-common phrase “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme” is all too real in the current anti-war, anti-genocide protest encampments that have erupted on college campuses.

Much like the anti-war movement in the 70’s, these student groups are speaking truth to power, demanding that universities divest from companies which benefit from genocide. It is important to note that divesting from these companies is not a difficult task. Many universities divested from Russian companies two years ago when Russia invaded Ukraine. This was swift action taken because these universities did not want to support companies that benefitted from this atrocity.

So how are universities responding to these calls for justice and divestment? After all, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a comparable situation to the Israeli occupation of Palestine.

University administrators claim to care about “safety” of all students, which is their reason for cracking down on the peaceful groups of students camped out on their lawns. However, the only violence being committed on college campuses is perpetrated by police who are called in by the universities to arrest and brutalize their students. In New York City, where these encampments began at Columbia University, the NYPD has not received a single report of violence from any protester. And yet, some states have threatened to call the National Guard to disperse these peaceful protests.

The reality is that these events have happened before. The song “Ohio” by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young is a protest song which references the trajedy of when the National Guard opened fire on peaceful protesters at Kent State University on May 4, 1970. Four were killed and many more were injured. It did not have to be that way had Kent State allowed free speech on campus.

What is particularly ironic about our inability to learn from history is that many of the university administrators who are authorizing these crackdowns on student free speech in the name of “security” would have been in college, or around college age, at the time of the Kent State shooting. They, of all people, should know that bringing police to campus makes students unsafe.

In order to protect students from police violence, community members have attended these college encampments in solidarity. In many cases, these community members have stopped further police brutalization because of their presence.

These professors, parents, and alumni refuse to be complicit in systems which fund and profit from the genocide of others across the globe. They are living antiracist values and being co-conspirators.

Last Thursday I spent the early evening observing young children, ages 2-4, at an early childhood center. It has become impossible for me to look at those young children without getting flashes of the dead and traumatized children who have been dispraportionately killed in Gaza.

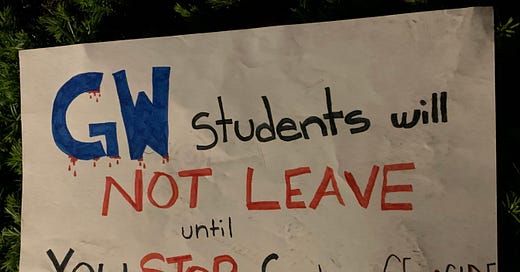

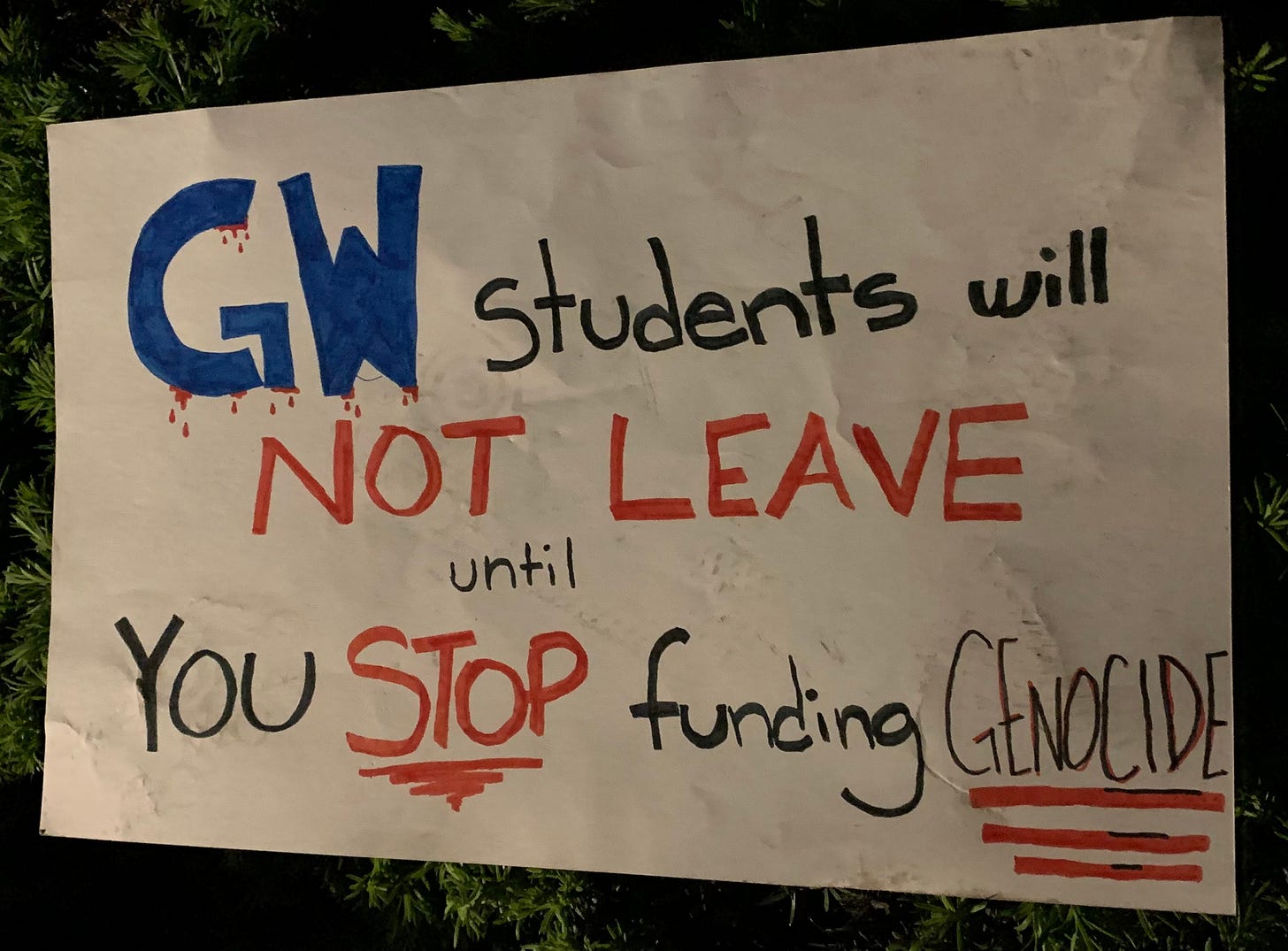

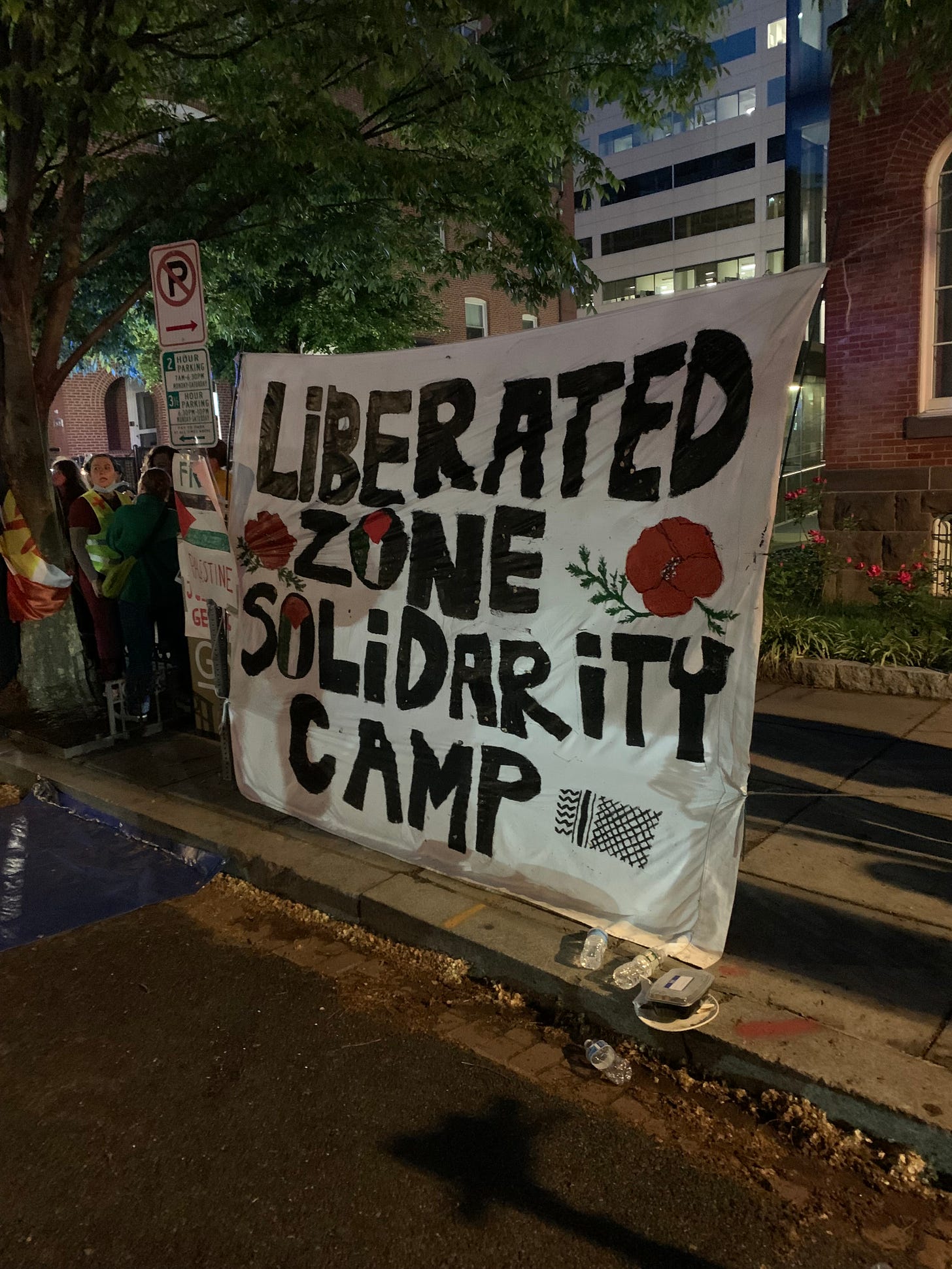

That same day, students at George Washington University set up an encampment demanding divestment from companies which profit off of Israeli apartheid and genocide.

I skipped my evening class to attend this protest for two reasons. First, because I simply cannot bear to do nothing while my tax dollars fund the bombing of children in Gaza. And second, I was prepared to put my body on the line and risk arrest to protect the undergraduate students and their cause.

The calculus was simple and is an evolving personal philosophy that I am developing:

My life is very short and a small blip in the history of humanity and the universe at large.

Given this fleeting existence, I refuse to be complicit, silent, or selfish, and will instead dive head first into shaping my existence in such a way that it benefits the lives of others and creates a more equitable world. My liberation is bound up with the liberation of others.

In the case of defending students from police, I would rather get arrested brave young people than prioritize my own comfort while Palestinian civilians are killed with my tax dollars. By joining a broad coalition, there is nothing to lose for me, and everything to gain for humanity.

Montessori, Morality, and Me

Another reason I decided to skip my class was because of the text I read in preparation for that particular evening, which was a paper by Dr. Montessori titled “Moral and Social Education.”

The foundation of Montessori education is that if we allow children to develop optimally, their innate human drive to create equitable systems of interdependencies emerges. They develop social cohesion and a sense of familial love with their peers and, by extension, all living beings.

In order to actualize this reality, Montessori argued that morality should be a key part of education. Rather than seeing morality as a particular set of rules, Montessori wrote that “the meaning of morality is our relation with other people and our adaptation to life with other people. Therefore, morality and social life are very closely united.” If we are aiming to support students in creating a society that does not yet exist, that is more equitable and allows each human being to meet their fundamental needs, they must have a moral code which values all life and strives for equality and interdependence.

How does Montessori suggest we support children in developing such a morality?

Montessori’s words cut against the grain of nearly all voices in traditional education. She wrote, “I am certain that it is but an illusion to believe that by teaching certain principles the world will be better… Our task is to give help to the child and watch for what they will reveal to us.”

To the traditional educator, this may seem counter-intuitive. We believe that morality is important, but we cannot improve the world through the teaching of morality? How else can we expect students to learn things unless we teach them??

The reason this statement is so powerful is because if we define morality as Montessori does, it is developed not through lecture, but through experience. And through the experience of developing community in a properly prepared environment, young people show us higher levels of social interdependence than we are capable of envisioning. Montessori argued, and I agree, that if we want to develop greater moral clarity as a society, we must look to young people and what they reveal to us. We must be prepared to shed our preconceived notions of what is acceptable, moral, normal, and embrace the societal transformation that young people can bring about.

Young people across the US and across the world are (and have been) showing adults higher levels of morality, of social interdependence and collective responsibility, and adults refuse to listen.

Take Greta Thunberg, who began her climate activism as a teenager, and was seen as an overly idealistic radical who “couldn’t possibly understand” the issues because of her age. As her activism has only increased, we have a much more positive view of her. Yet this cultural attitude still persists because she refuses to work within the system for a cause which can’t wait.

I was shocked by the interdependence that I saw at the George Washington encampment. Community members came out in droves to provide food, first aid, and other supplies which were freely available for all who needed them. Organizers passed out masks and mingled through the crowd, offering support and monitored the safety of the event. There were regular chants of, “we keep us safe!” Indeed, the only threat to safety for these students was from police and university administrators who are attempting to silence these voices with arrests and violence.

Confronting White Supremacy; or Why My Comfort Isn’t Important

One of the core tenants of white supremacy culture is the idea that those who are white have a right to comfort which superceeds the right of the oppressed to openly discuss and change their circumstances. The result of this is anger and frustration directed at the person calling out the issue of oppression, rather than anger at the oppression itself, therefore silencing any chance of ameliorating the conditions.

What this culture of comfort does, ultimately, is it convinces us white people that what we gain from these systems of oppression is better than a world without such oppression. Yet this is a lie. White supremacy culture is toxic for all- even those who benefit from it.

To quote Tema Okun:

White supremacy culture invites white people into a silencing, a numbing, and a disconnection from our basic humanity in service of a false safety based on the idea that those of us who are white are both better and normal. Being encouraged into this ideology might offer short-term satisfaction and material gain, yet I agree with public theologian Ruby Sales, who tells us that “whiteness is a death sentence.” We see this death sentence reflected in the extremely high addiction, suicide, and depression rates in the white community. The generational legacy and price of gain based on the psychic, mental, physical, and spiritual violation of others is a heavy one. (White Supremacy Culture- Still Here)

My comfort is not worth the genocide of tens of thousands of civilians in Palestine. In fact, as I’ve been doing my own antiracist work, I feel a need to engage in further activism because my “comfort” is hollow when it comes from white supremacy.

I have no answers, only more questions

What kind of teacher would I be if I were not prepared to put my body on the line for my students? For years I have played out scenarios in my head about how I would defend my students if there was an active shooter on our campus.

If I am willing to put my body on the line for my students in that situation, why wouldn’t I do the same for children in Gaza?

How could I justify my position as a professor and teacher if I wouldn’t defend students who are organizing for a better world, and do everything I could to prevent them from being brutalized by police?

I’ll leave you with a quote commonly attributed to Lilla Watson:

"If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together."

I will continue to spend my open moments doing everything I can to protect students who are calling for justice, because I refuse the toxic agreement of white supremacy culture.

I have everything to gain from fighting for collective liberation.

What will you do?

While I believe that what you did was brave as well as right, I am also confused about whether it helps the cause you feel for. I read Nicholas Kristof’s article (https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/01/opinion/student-protests-gaza.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare&sgrp=c-cb) and I thought he was right too.

It is a difficult time in the world and my heart goes out to all the suffering. I can’t alleviate the suffering so I tend to just work harder on what I can do instead which is the slow building up of peace for the future.