Educators: Are You a Choreographer or a Coach?

Pushing teaching and learning toward authentic self-direction

In my early years as an educator, I worked tirelessly outside of school hours to develop my curriculum and pedagogy. On one night in particular, I was struggling to develop the perfect plan for the following day. As it was getting late, my wife asked me:

“Why can’t you just give them something to do? Why do you have to lead them through everything?”

At the time, I wrote off her question as a misunderstanding of my role. I firmly believed that as a teacher, it was my job to craft each moment of learning for the students in my care. While my students were active, at this stage in my teaching they were only active in ways which I prescribed.

Looking back, it’s clear that in my early days of teaching I fell into a common trap, which Phillips Exeter instructor Nina Pettigrew calls the “teacher as choreographer.”

In her essay, “The Art of Listening,” Pettigrew reflects on her early years as an educator, writing “I never entered the classroom without knowing my goals… I thought carefully about the steps by which I would bring my charges from point A to point B or C or D. I thought of myself as a coach, but in fact I was a pretty good example of Teacher-as-Choreographer. The students did the dance, but I controlled the music and the steps they took… I was active and my students, though lively, were passive- ‘little pitchers’ into which I poured all my bright ideas.”

It is easy to become a “teacher as choreographer” because this approach is built on the same core beliefs about students as traditional education: Namely that unless they are directly told what to do, they will be aimless, waste their time, and not “learn” anything. Of course, this is simply not the case, yet this attitude persists.

And yet, these were the subliminal ideas that I too held. During my first year of teaching full time in a Montessori adolescent program, I was urged by a colleague to use the Harkness Discussion method with my students. The Harkness Method allows students to have fully student-led discussions on any type of text, without any interference from the teacher. My initial reaction to my colleague was disbelief:

How is it possible that students could have a discussion entirely on their own? How would they know what to do without me telling them?

Despite my serious hesitations, I decided to try the method with one of my classes. I prepared them well, told them the expectations, and sat back to let them discuss. I was used to traditional Socratic discussions, where I asked all the questions and often had to “pull teeth” to get responses. I didn’t know what would happen next.

Silence.

One minute passed, and I was getting antsy, but I had promised myself that I would see this through at least once. Another minute passed, and students continued to look at each other. I could see the beginnings of non-verbal communication between them. Finally, one student jumped in.

“Ok guys, where should we get started?”

And they were off!

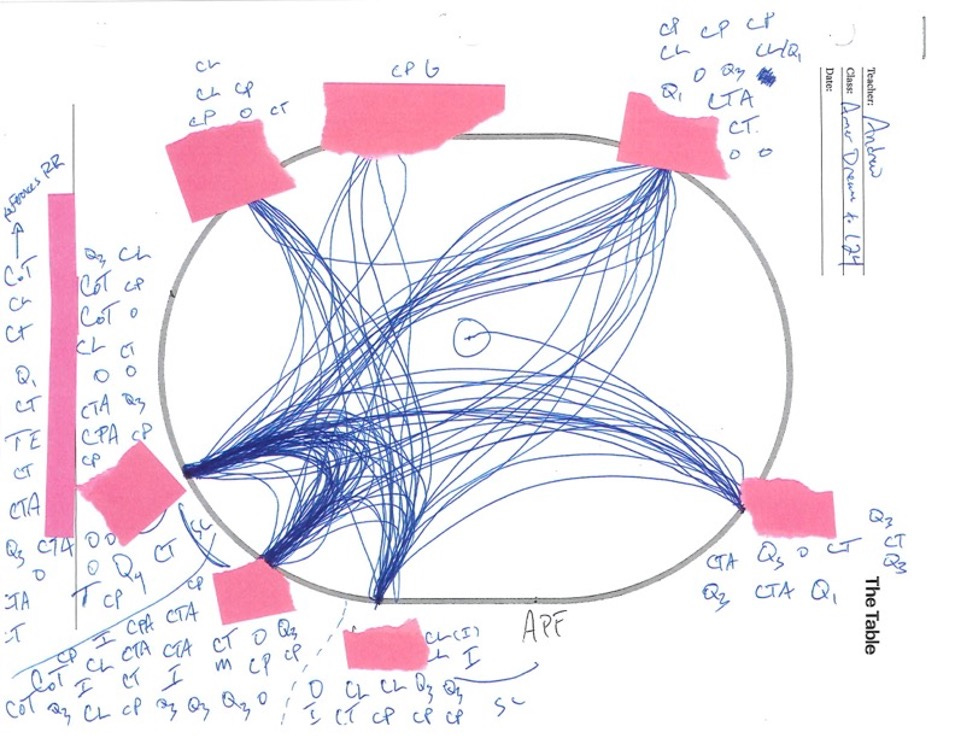

Students who were strong participants shared their thoughts confidently. Students who I had never heard from before in class also chimed in. The dialogue was thoughtful, organic, and the students were in charge of it all. I took feverish notes of their discussion, sitting in disbelief at my students ability to self-direct. I left the class energized in a way that I had never felt before. Not only could my students handle the responsibility of leading a discussion on their own, it was the best discussion we had so far that year.

It made me ponder the question: How can I prepare the environment to foster the maximum level of student self-direction?

This was the start of an avalanche of change in my teaching practice.

I soon realized that the Harkness Method is built on the same fundamental principles as the Montessori Method, which is why it fits so seamlessly within the method for adolescents. Both methods posit that if we prepare an environment which meets the needs of the students, they will be able to independently self-direct their own learning and achieve levels of depth and insight that would not have been achieved in a traditional setting. If we can tap into students’ intrinsic motivation to learn, anything is possible.

Over the years, my role has shifted significantly from a “choreographer” to a coach. I prepare an environment, observe my students as they self-direct, and act as a coach and mentor to them along the way. As the coach, my role in the classroom has fundamentally changed. I am not “in control” the way I used to be, and I love it.

If you were to come and observe my classes, you would most often find the room(s) buzzing with independent and interdependent self-direction, and after some searching, you would find me dialoguing in a corner with one or two students at a time. What I learned from that very first day with the Harkness Method is that, if I prepare the proper environment for student self-direction, they don’t need me to direct their every move. In fact, since I’ve transitioned my pedagogy in this way, the work my students do regularly exceeds my expectations.

One of my favorite examples is of a seventh grade student who wanted to learn about modern day capitalism. He was a strong reader, so as his coach and mentor, I told him that if he wanted to understand modern day capitalism, he had to learn about neoliberalism. So, I gave him A Brief History of Neoliberalism by David Harvey, a book I read in college, asked him to read the introduction, and get back to me. By the end of the week, he reported to me that not only had he finished the entire book, but he had done significant additional research, because neoliberalism as a topic fascinated him. He ultimately decided to give a 15 minute presentation to our school community on the topic, which was at the level I would expect from an upper level high school student. In seventh grade. And none of this work was required! He was inspired to create this project out of his own intrinsic drive to learn. This is the beauty of a developmentally appropriate, self-directed environment.

If I had not “let go” of being in control of my classroom, none of this would have been possible. In my work with teachers in public and private schools in the U.S. and China, I have found the “letting go” step to be the hardest, if not impossible, for some teachers, even for those in Montessori and progressive environments. Everyone wants their students to do great work, but in order to get there, we have to put our egos away. This a dimension of what Maria Montessori called the “spiritual preparation” of the educator- more on that in another post.

If you’re having trouble “letting go,” and you’re reading this, give it a try- not because students will always do things your way on your timeline, but because they will come up with possibilities that you could not have considered.

Thank you, Andrew. You’ve helped distinguish various aspects of teaching….and aspects of Life. We often try to control the dance of Life, but when we let go, it really feels good to dance! Same with teaching in a classroom!

Beautiful! I finally got a chance to sit down and read this, and it resonates on many levels. I'm thankful that you have the gift and motivation to give language to these ideas.