Beyond the Writing Workshop: Literacy Pedagogy for Human Development

How a student who loved writing, but hated writing for my class, changed my pedagogy for the better

Have you ever groaned when you were given a writing assignment in school?

Have any of your students groaned when you give them a writing assignment?

If you’re reading this blog, and have grown up in the American schooling system, you probably fall into one of these categories. This post dives deep into writing pedagogy: How it’s usually done, why that method often fails most students, and a new vision toward writing pedagogy which centers human development.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

It All Started With a Groan

My journey to transforming my writing pedagogy began with the groans of one particular seventh grade student, Marie (a pseudonym), who I met in my first year starting a Montessori adolescent program. As one of two core faculty, I was responsible for designing and teaching all of the humanities. I had been looking forward to working with Marie, who was an avid writer. She filled up dozens of notebooks with her stories and illustrations, demonstrating a strong intrinsic drive for writing in verbose, expressive ways.

So why was she groaning about writing in my class?

In fact, she was not only groaning- she was dragging her heels on the five paragraph essay on her family history that I had assigned to the point of trying to avoid its completion. The student who wrote feverishly outside of class was actively resisting writing in class. Something was wrong and I knew I had to change it. I had to reframe my writing pedagogy around two key questions:

How do I prepare an environment where students intrinsic motivation is sparked?

AND

How do I fuel students passions, like Marie, rather than smother them?

My first step, suggested by a colleague of mine, was to write the essay alongside my students and invite them to do a peer review on my essay. This invaluable exercise did two things. First, it greatly enhanced my relationships with my students, who saw me putting in the same effort I was asking of them. Second, I realized that the way the assignment was structured was boring and stifling to creativity. I knew that I could no longer resort to teaching writing how I had been taught.

Re-Centering on Self-Expression and Self-Construction

To begin my journey of reinventing my practice, I went to Maria Montessori’s work on adolescent development and language. Montessori described language, along with math and moral education, as a “psycho discipline,” meaning that language is a tool which humans use to develop themselves, and their relationships, in the world. In other words, literacy is a social practice, which is deeply tied to self-expression and self-construction, particularly for adolescents who are building new identities as they move toward adulthood.

If we are to view literacy as a social practice and the means through which adolescents construct their personalities, it is clear that a “one size fits all” essay, like I had assigned, was not going to fit the bill. Sure, each student could customize what was written within the five paragraph structure. However, a key task of adolescence is to understand and communicate the new and intense emotions that they feel, which are unique to each individual. To only provide “one avenue” for that self-expression is to automatically alienate the majority of students who simply need to explore and play with language for the purpose of self-expression and self-construction. In order to foster the intrinsic motivation within my students, I needed to open the floodgates to what was possible with language.

So what does a new vision look like?

There are three other thinkers whose work, along with Montessori’s, I combined to create a cohesive vision for a literacy program that is rooted in students developmental needs and the intrinsic motivation that adolescents have. Those thinkers are John Warner, James Moffett, and Maja Wilson.

First, We Must Abolish the Five Paragraph Essay

“But Andrew” says the concerned writing teacher, “if we don’t give students the five paragraph essay, they won’t ever learn the fundamentals of writing! They won’t know what to expect when they leave your beautiful Montessori program and enter the ‘real world!’”

To the first point, I respond with a question to the reader.

When have you ever seen a professional publication use the five paragraph essay?

You haven’t- and that’s because it was invented by teachers to grade papers easier. This is the same reason why rubrics exist; not because the five paragraph essay and rubrics teach students fundamentals about writing, but because they make grading dozens of essays easier by eliminating any kind of human response to the writing. For those interested, this is documented in Maja Wilson’s book Rethinking Rubrics in Writing Instruction.

Not only does the five paragraph essay not help students, many argue that it actually hurts their true ability to write. This was the experience of college writing professor John Warner, who documents the phenomenon in his book, Why They Can’t Write. He explains that throughout a traditional high school English curriculum, students have been taught to look like they’re writing, by plugging ideas into a highly formulaic structure like the five paragraph essay, and increasing the length of those essays as they progress in high school. This type of formulaic writing hurts students writing abilities because they are prevented from exercising the single most important skill that real writers use: choice. Writers have to think critically about the placement of each word and how it will impact the reader and their message. These choices eventually allow the writer to develop a unique style and to spread their messages in a way that only they can. And yet, the way we often teach writing allows for none of this. These students who have done “pretend writing” all through high school arrive in college waiting to be spoon fed directions, only to flail in the absence of them.

Without the Five-Paragraph Essay, What Do I Teach?

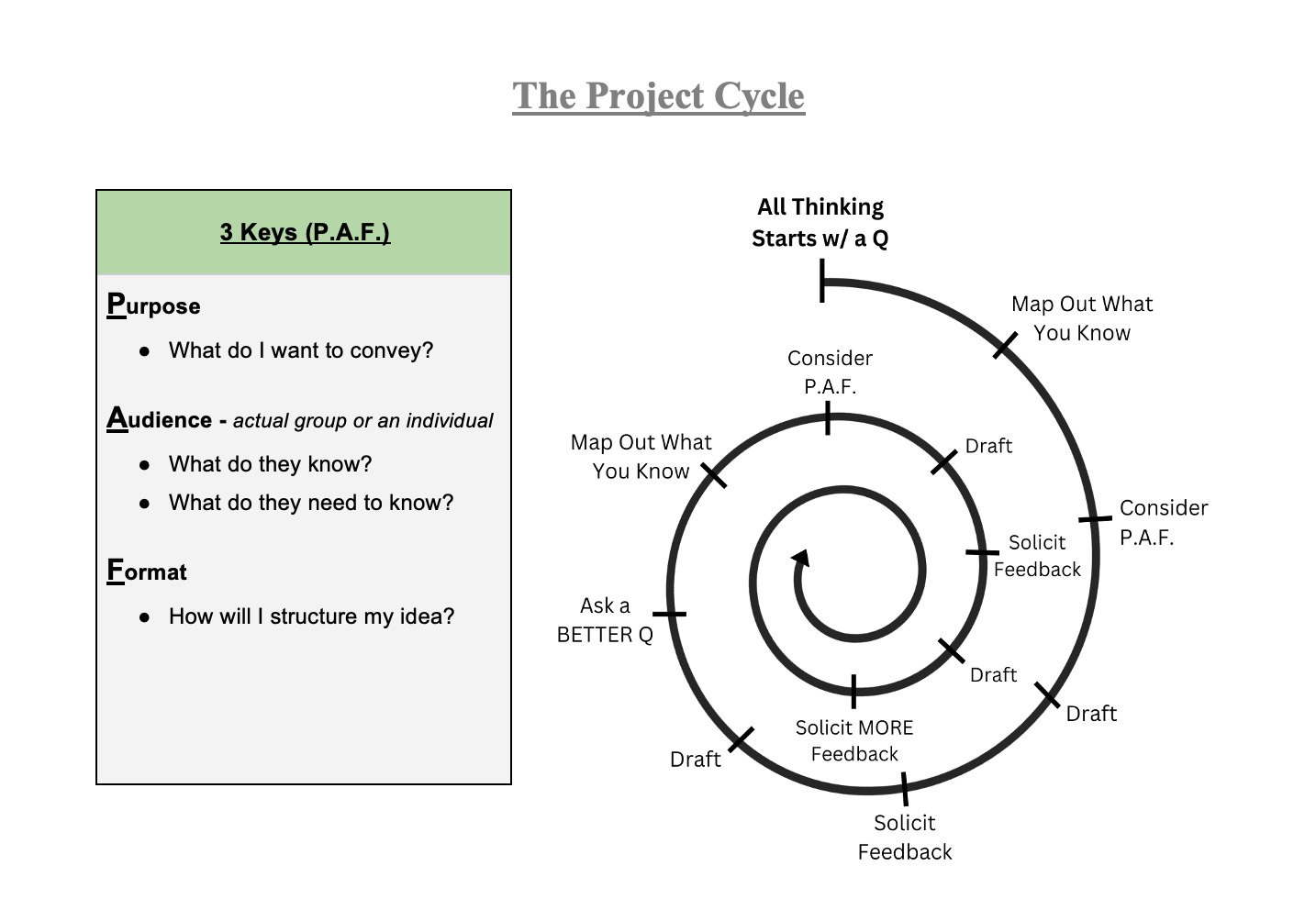

The key area where Warner, Moffett, and Wilson overlap is on the three keys to writing: Purpose, Audience, and Format. Every piece of writing- from a text to a doctoral dissertation, involves the author making choices around these three keys. The author must know their purpose and why they are writing. They must know their audience, what they already know, and what they need to know in order to understand the purpose. Finally, they must manipulate the format of their piece to meet the needs of the audience so that the purpose is clear.

Now, as I teach writing across the humanities, I introduce students to the three keys, and then I prepare an environment where they have to make intentional choices in their writing. Each student is also in close dialogue with me throughout the process, so they can talk through their choices and I can provide feedback. Rather than the “one and done” model of traditional education, each piece of writing is cyclical, with students constantly engaged in revision and reflection, recognizing that no piece of writing is ever complete.

A 30,000 Foot View

After doing intensive reading, my pedagogy changed in significant ways. Here are the fundamental pieces which now inform my work:

Underlying Principles:

Engagement and depth of work is directly correlated to the level of autonomy, independence, and choice that students have.

Students need time and space to “come to the work,” and the guidance from the adults should be gentle, allowing for intrinsic motivation.

True, authentic growth will be non-linear, and that’s OK!

The Vision for Language Arts and Humanities:

Student projects have broad parameters so that:

Students can self-direct their learning.

Students are responsible for their own learning.

Students experience the difficulty and reward of creating unique work, rather than following a predetermined path which is difficult and more complex than “following the directions” of a teacher-led project.

The curriculum is naturally scaffolded to promote comfort with greater and more specific audiences, so that students are constantly considering the three keys to writing (Purpose, Audience, and Format). The writing curriculum is based around students making choices in their writing around these three keys.

The curriculum should incorporate significant opt in opportunities, which is where students’ best work often occurs

The guide should intentionally co-create the course along with students.

The environment and peers are the best teacher, and the guide should actively prepare the environment to maximize peer and environmental learning, and practice “minimally invasive teaching.” (More on this in a future post!)

Does it Work?

When we last left Marie, she was groaning because of the writing I had assigned. As I made these changes and shifted my pedagogy, her attitude toward writing in class shifted as well. Her fire for writing not only came back, but expanded, leading her to develop a stellar portfolio and entrance to an elite writing program. Each student, no matter their previous interest in writing, found their intrinsic sparks. And the results spoke for themselves: In the four years of experience teaching middle school outside of Montessori, I had never seen such sophisticated writing from students at that age across the board. The beautiful thing is that when we focus on the students developmental needs, and center their self-construction, we allow each of them to find the path that they need.

No Groans Needed!

When I transformed my writing pedagogy, it also pushed me to transform all of my pedagogy. I was able to prepare an environment that was designed to meet the needs of the students in my care and allow them to make meaningful choices in their work. Unlike most middle schools, my students were happy to arrive at 8:00am every day. Often they would burst through the door, clamoring to get started on projects or activities in the community.

What my students and I created together, through a process of co-construction, was not static and ultimately cannot be fully captured in writing. The only way I can describe it is that the curriculum and pedagogy lived and breathed among and within me and my students. It is not something that can be “transplanted” somewhere else, because it responded to those students at a particular time and place. However, the principles still apply, and for those willing to take the leap, whatever you and your students create together is bound to be meaningful, because it lives among and within each of you.

Texts referenced, for those interested

From Childhood to Adolescence by Maria Montessori

Why They Can’t Write by John Warner

Rethinking Rubrics in Writing Instruction by Maja Wilson

A Student-Centered Language Arts, K-12 by James Moffett